No. 35, Summer 2006

Clayton Kratz: Went to Russia 1920

In the cemetery of the Blooming Glen Mennonite congregation in Pennsylvania stands a memorial marker with a simple inscription: “Clayton Kratz, Nov. 5, 1896. Went to Russia 1920.” It is a silent tribute to a remarkable young man whose fate remains unknown. Kratz, along with Arthur Slagel and Orie Miller, were the first three Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) volunteers. Even before the fledgling MCC had an executive committee or a proper organizational structure, they were sent to investigate the needs of Mennonites suffering in the emerging Soviet Union and to bring relief assistance.

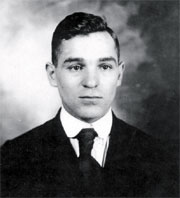

Clayton Kratz

The trio left the United States on September 1, 1920 for Constantinople. Kratz, Miller and Slagel were all members of what was then commonly referred to as the (Old) Mennonite Church. Constantinople was a logical place to investigate possibilities of assisting their co-religionists in southern Ukraine, because American Mennonites since the 1890s had a history of working in Turkey in conjunction with the Near East Relief Committee to meet the needs of victims of the Armenian–Turkish conflict.

Constantinople, however, was to be only a way station. It was the place to gather supplies and be the base station from which to reconnoiter the desperate conditions facing the Mennonite settlements of south Ukraine. The cumulative impact of World War I, the continuing Civil War between the Red Army (forces loyal to the new Bolshevik government), the White Army (forces opposed to the Bolshevik), marauding and destructive paramilitary bands, an epidemic outbreak of typhus and malaria, and an extended drought had all left the population on the brink of starvation.

MCC was just emerging in the summer and fall of 1920. A summer meeting in Elkhart, Indiana brought together representatives from many local relief committees concerned about the fate of their Russian brothers and sisters. Even as the three traveled toward Constantinople, a second group of various denominational representatives met in Chicago to officially constitute the organization. So the three representatives went, carrying the compassion and commitments of a united Mennonite community in North America.

Kratz, at twenty-four, was the youngest of the three representatives, all of whom were still in their twenties. He had finished his third year at Goshen College. A student leader and engaged to be married, Kratz had a promising future ahead when he embarked on this mission to needy co-religionists in a far-off land. Upon arriving in Constantinople, Slagel remained to organize the shipment of relief goods. Miller and Kratz proceeded on with hopes of visiting Halbstadt and Khortitza, the administrative centers of the largest Mennonite colonies in Ukraine.

In the fall of 1920 the Civil War was raging in Ukraine and the Molochna and Khortitza colonies were right in the line of battle between the Red Army, the White Army and the para-military band of Nestor Mahknov. The lines of control between these three forces shifted back and forth. Mennonites were caught, not knowing from week to week who would be in control.

Miller and Kratz, after assessing the needs of the Molochna colony, proceeded north toward the Khortitza settlement. Military engagements, however, made it impossible to get to the Khortitza villages adjacent to the Dnieper River. Forced to turn back they retreated to the Molochna villages. Miller returned to Constantinople. Kratz was urged to move to the safety of the Crimea. However, he thought it would be cowardly to forsake those whom he had come to assist. Within days the Molochna was overrun by the Red Army. Kratz and a companion were arrested and then released. A few days later he was arrested again. This time he was not to be released despite the pleas of local Mennonite officials. Together with other political prisoners he was taken away. No doubt he was considered to be a spy of the American government.

Clayton Kratz did not come back. Perhaps time will yet reveal the texture of his final days. What we do know is that his sacrifice helped to infuse idealism into a fledgling organization. Today MCC, with its motto “In the Name of Christ,” brings food and medicine to the needy, empowerment to the weak and marginal, reconciliation and hope to the alienated and despairing peoples around the world. Kratz’s life helped twentieth century Mennonites to rekindle what Menno Simons called “true evangelical faith [which] cannot lie dormant.”